Fruits as Mental Maps: Taste, Memory, and Meaning

What a Persian film, a Russian short story, and a Swedish director taught me about how taste triggers memory

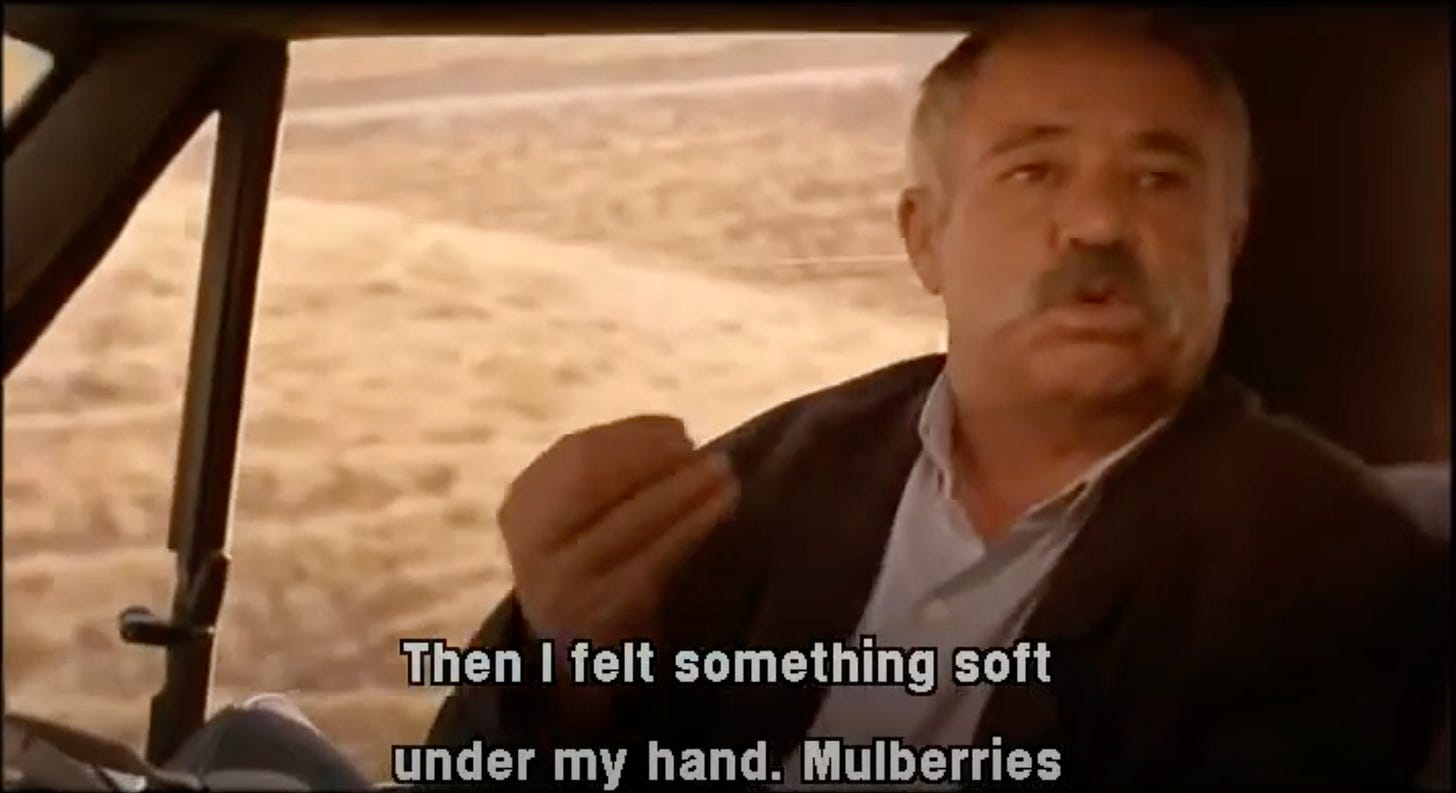

Two weeks ago I went to see Taste of Cherry by Abbas Kiarostami.

The movie felt a bit long honestly, but the photography was awe-inspiring. After the credits, I found myself thinking about one specific scene way more than I would have given it credit for.

The Turkish man tells about how a mulberry saved his life:

" I was so fed up with it that I decided to end it all. One morning, before dawn, I put a rope in my car. […]. Then I gathered some mulberries to take them home. My wife was still sleeping. When she woke up, she ate mulberries as well. And she enjoyed them too. I had left to kill myself and I came back with mulberries. A mulberry saved my life. A mulberry saved my life.”

But it made me think of another famous berry in literature: Chekhov's "Gooseberries." (full text in this link). The brother of the narrator imagines his life and wants a farm:

"He could not imagine a homestead, he could not picture an idyllic nook, without gooseberries."

Later, when he finally achieves his dream and tastes his own gooseberries: "They were sour and unripe, but... he ate them greedily, continually repeating, 'Ah, how delicious! Do taste them!'"

And Bergman's Wild Strawberries. A little quote to introduce their importance:

Professor Isak Borg: "The place where wild strawberries grow! Perhaps I got a little sentimental... the day's clear reality dissolved into the even clearer images of memory that appeared before my eyes."

So much for berries. It’s just a fruit. So why berries?

The Mapping Theory

I think what's happening here is more complex than simple symbolism. These fruits function as activation points in what I call "memory networks”. I am talking about the networks of sensory experience, memory, and meaning that our brains build over time. Those are hidden in us in many ways, integrated.

When we encounter certain tastes, textures, or smells, we don't just experience them in isolation. Our minds activate entire webs of association that have been built through repeated experience. The fruit becomes a portal into a whole embedded reality.

Let me try mapping out what each character might have built around their fruit.

This is just my take.

Mr. Bagheri's Mulberry Map:

Sweetness → Life worth living

Tree climbing → Childhood play/safety

Dawn light → New beginnings

Taking fruit home → Providing for family

Wife enjoying them → Shared pleasure

Nikolay's Gooseberry Map:

Sweet Berry → Achievement of dreams

Own land → Independence/success

Farm ownership → Escape from bureaucracy

Self-sufficiency → Personal worth

Professor Isak Borg's Wild Strawberry Map:

Summer berries → Childhood innocence

Wild growth → Natural, unforced happiness

Small, delicate fruit → Precious, fleeting moments

Sharing with cousin → First love/intimacy

My Taste of Cherry

My grandparents would take us there with my brother and sister every summer. The house was one of those old stone Normandy places with blue shutters and a veranda that creaked when you walked on it. I have scattered memories. Reading 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea under that veranda when it was raining. I couldn’t really understand the book at the time but I remember the slightly damp pages from the sea air and the cool cover . Losing (often) at tennis against other kids and being a sore loser about it. Watching the Tour de France on TV after eating melon with ham.

Every afternoon, we'd walk to the beach. The path wound past these imposing houses overlooking the coast, grand Belle Époque villas with their manicured gardens and wrought-iron gates. Near the Cabane Vauban, where old German bunkers still jutted from the cliffs.

One element that captured my attention was one particular house with a cherry tree that seemed impossibly tall to my child mind. Not just tall, ancient, with thick branches that sprawled in every direction and a trunk so wide I couldn't have wrapped my arms around it.

The cherries hung like tiny lanterns, deep red and glossy, catching the afternoon light. They were just out of reach from the ground, which made them infinitely more desirable.

I remember we were invited to that house at some point. Friends of my grandparents maybe ?

The cherries were perfect not too soft, not too firm, with that particular sweetness that only comes from fruit picked at exactly the right moment. But it wasn't just the taste. It was the weight of them in my small hands, the way they stained my fingers pink. The way my grandmother would smile when we would show her proudly what our little hands had tentatively picked up.

My Cherry Map:

Normandy → Family time/security

Summer timing → Best season of the year

Warm weather → Freedom from school

Tall tree → Being small and the world being so big and exciting

Every time I eat cherries now, I don't get a simple Proustian flashback. Instead, my embedded reality shifts. I'm pulled back into a mental state where the world feels safe, beautiful, and full of simple pleasures. Like a Normandy summer afternoon.

Exactly like Isak Borg in the Bergman movie quoted earlier. (“the day's clear reality dissolved into the even clearer images of memory that appeared before my eyes.")

Funnily, I associate Nectarine to the Pyrénées-Orientales and to my other grandparents… but that’s another story.

But why berries: Back to Reality

Fruits are perfect for this kind of mental mapping because:

Seasonality: They mark specific times of year, anchoring memories to cycles of abundance and scarcity.

Pure Sensation: Unlike complex foods, fruits deliver straightforward sensory experiences: sweetness, texture, juice. They bypass intellectual analysis.

Temporality: They ripen perfectly for brief moments, then spoil. This embodies the transience that makes experiences precious.

What makes these fruit moments so powerful in the stories is how they function as emergency resets for the characters' mental maps.

Mr. Bagheri, in his suicidal despair, has lost access to what he believes makes life worth living. The mulberry doesn't just taste good. It reactivates his entire network of life-affirming positive associations. Suddenly he remembers what it feels like to provide, to share joy, to be part of a community.

Nikolay's gooseberries work differently. His map was built on fantasy rather than genuine experience, which is why the fruit is sour and disappointing. But his embedded reality is so strong that he experiences them as delicious anyway. He's enjoying his dream, not the actual fruit.

His mental model of the farm/world is so strong that he easily bypasses the sour taste of the gooseberries. I genuinely believe that to him the gooseberries taste great. We will explore this in more detail next week where we dive deeper on the brain processes behind these models.

Different Experiences

What I find fascinating is how we build different emotional and memory maps around (probably roughly) the same sensory inputs. My cherry map might share nothing with yours except the basic taste of cherries.

This is why these fruit scenes work across cultures and contexts (here: Iran, Russia, Sweden). The specific associations don't matter, what matters is that we all build these sensory-memory networks, and we all sometimes need to be pulled back into them.

Next time you eat fruit, pay attention to what gets activated in your mental map. Notice how the taste pulls at threads of memory, season, emotion, and meaning. You might discover your own memory network hiding in something as simple as a cherry.

And sometimes, when we've lost our way, we need something as simple as a mulberry to remind us what it feels like to be alive.

![Taste of Cherry (Criterion Collection) [Blu-Ray] Taste of Cherry (Criterion Collection) [Blu-Ray]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!1ytt!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F68a90f80-09c3-4ef4-93a6-66db0c87fc4d_805x1000.jpeg)

In the way you put it: those memory networks act as significants that are created on the instant we feel them through an experience or are they anterior to it? Let’s put it this way with an example: the significant brings you to two types of ideas.

1) The remembrance: a kind of idea that is anterior to the significant as it is linked to it’s usual properties and past-iterations ( the berries you eat remind you of the berries you ate and the cognitive environment / ideas of said experience) therefore the signified is strictly anterior to the significant and simply revigorated by it.

2) The created one: it is a new idea that is not anterior to it’s significant. It is created through the stimuli of the significant; with it being impactful enough to generate a new sentiment: ( the berries confirm the fact that something ended or has been achieved such as the fact that you finished school or can taste the fruit of your hard work, provide for your family etc…) those are deeds that did not exist in the same form ( feeling of finishing school does not feel the same when you get out of the building as when you eat a summer aliment in Normandy ) or did not exist at all ( providing for his family ). Therefore, through this apellation of « memory networks » it is implied that it is from the memory that the significant brings the signified while in fact it could be both from the memory and from the very significant itself.

I would have now liked to explain the importance of time in that matter and the way it can be measured, allowing to determinate more clearly where the creation act takes place ( Qui peut dire où la mémoire commence;

Qui peut dire où le temps présent finit?

Où le passé rejoindra la romance,

Où le malheur n’est qu’un papier jauni. »)

But such outrageously interesting concepts could only be roughly treated in a comment section. Therefore I will stop this already lengthy comment as it is, hopefully it was constructive or at least intersting.

J’ai beaucoup aimé, je me permet d’y aller à nouveau de mon commentaire un peu envahissant mais sache que je le vois comme une marque de respect pour ces sympathiques réflexions et leur auteur. J’ajouterai que je ne suis pas insensible non plus au goût d’un brugnon frais de la Vallée Heureuse.

Less juicy, but not less powerfull les coquillettes au beurre remind me of the winter season in Issy les Moulineaux 😋